Last week, Jacob Blake was shot seven times in the back by a white police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The incident immediately prompted a boycott by three NBA playoff teams currently “in the bubble” (isolation protection from COVID-19) in Orlando, Florida. The upcoming presidential election and recent events during the pandemic have given sharper focus to the unresolved issues of social injustice and economic inequality in America. Racism exists nearby and within, then, and now. It resides in our hometowns and homes across America. Today, we will explore Jackie’s Pasadena during the 1930s and 1940s.

BROOKSIDE PARK, PASADENA (CALIFORNIA)

Less than a century ago, a local baseball field and city plunge became a social injustice flashpoint in America.

Timeline: The Brookside Ballfield

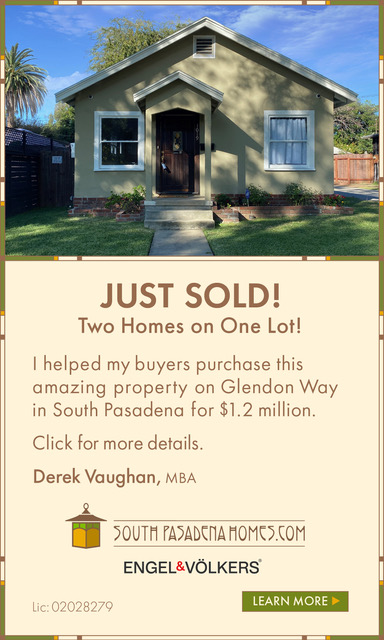

The Chicago White Sox held their spring training camp at Brookside Park in Pasadena, California (1933-42 and 1946-52). To accommodate professional baseball, the City of Pasadena authorized funding for significant ballfield improvements, including permanent stands for spectators made of arroyo stone and reinforced concrete.

Meanwhile, local resident Jackie Robinson was quickly building a reputation for his athletic ability in baseball, football, basketball, and track. In 1936, he earned a place on the Pomona annual baseball tournament all-star team along with future Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Bob Lemon. Robinson made the All-Southland Junior College Team and was selected as the region’s Most Valuable Player.

On March 13, 1938, Robinson’s Pasadena City College team played an exhibition game at the Brookside Park ballfield. He had two hits in a 3-2 loss to the major league White Sox in 11 innings. In that game, the White Sox team manager, Jimmy Dykes, was so impressed with Jackie he reportedly said: “If that boy was white, I’d sign him right now.”

On March 22, 1942, Robinson and Nate Moreland were allowed to warm up with the White Sox. Again, Dykes passed on the talented Robinson, referring to the “unwritten law that prevents negro players from participating in organized baseball.”

It would be another five years before Jackie Robinson would play Major League Baseball, becoming the first to break the color barrier in a sport segregated for more than a half-century.

Timeline: The Brookside Plunge

On July 4, 1914, a public swimming pool opened next to the baseball field. The plunge only allowed white people, except on Wednesdays during the afternoon and evening, and on the last day before the pool was cleaned.

In 1929, a black taxpayer group challenged the practice, and the City of Pasadena promptly prohibited all nonwhites from using the pool. In 1929, people of color were once again allowed to access the plunge but only on Tuesdays between 2 and 5 pm. The city’s concession came with the new name “International Day.”

In 1945, a successful lawsuit forced city officials to allow unrestricted use of the swimming facilities. However, the City of Pasadena immediately closed the plunge, citing that it was no longer financially viable to keep open a pool for public use.

Sammy Lee, the son of Korean immigrants, first learned how to dive at the Brookside plunge. Since he was allowed to use the pool only one day a week, he constructed a diving board and sandpit to train. Lee was the first Asian American to win diving gold medals in back-to-back Olympic games (1948 London and 1952 Helsinki). Lee said he was inspired to perform in the face of racist policies at the time, “I was angered, but I was going to prove that in America, I could do anything.”

My Neighbor William Sato

South Pasadena resident William Sato shared his experience of the train ride to the relocation camp: “I thought what’s going to happen to us? As we went over Cajon Pass into the desert, I remember thinking they’re going to put us in the desert, and they’re going to line us up and kill every God damn one of us.”

During the spring of 1942, about 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were rounded up by local authorities and incarcerated or sent to internment camps, many losing their businesses and homes forever.

The criteria that determined Japanese ancestry: “as little as 1/16 Japanese, orphaned infants, or even one drop of Japanese blood.” Sixty-two percent of the internees at the camps were United States citizens.

The San Francisco Examiner’s front-page headline read: “Ouster of All Japs in California Near!” Meanwhile, the trains arrived to carry thousands of our neighbors away to the internment camps – their home for the next four years.

Timeline: Change At Last

Jackie Robinson commented on the treatment of blacks while growing up in Pasadena, “We saw movies from segregated balconies, swam in a municipal pool only on Tuesdays and were permitted in the YMCA one night a week. In certain respects, people in Pasadena were less understanding than Southerners, and even more hostile.”

On July 7, 1947 (the year that Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball), the NAACP obtained an injunction that forced the Pasadena plunge’s reopening without restrictions based on race or gender.

On April 5, 1947, Jackie Robinson would put on uniform No. 42 and play major league baseball for a 10-year career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Robinson was named the MLB Rookie of the Year Award in 1947, was an All-Star for six consecutive seasons from 1949 to 1954, and won the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949. He played in six World Series, culminating in the Dodgers’ winning the 1955 World Series.

Robinson was hit by 72 pitches during his career, some as retribution for his skin color. His lifetime batting average was .311. He got on base nearly half the time he stepped up to the plate with an On Base Percentage (OBP) of .409. On January 30, 1988, the ballfield at Brookside Park was renamed Jackie Robinson Memorial Field in honor of the man who changed the game and race relations in America forever.

Author’s note: This story has special meaning for my family and me. My daughters are mixed races from different mothers, Japanese and Mexican. My youngest daughter just graduated from USC’s Thornton School of Music. She is a music composer looking for work in the male-dominated film industry.

Today, economic opportunities favor sufficiently motivated degree-toting white males. Their entrenched power and influence in business and politics shatters the myth that there is a level playing field in our modern society. There is no equity among race, gender, and age in the pursuit of the American Dream. Yet.

.png)