You had humble beginnings growing up in Chicago. What inspired your love of baseball?

My parents encouraged participation in life. And while neither was a die-hard baseball fan, both recognized my early interest in and affection for the game. Three of my dad’s brothers, Pasquale, Joe, and Frank, were passionate Cubs’ fans. Along with my parents, they took me to games, shared stories about baseball history, and increased my interest – all of which was rather remarkable considering that in this place and time, the family was trying to make a living and surviving with limited financial means. Regardless of their schedules, my uncles always found time, which led to the rare opportunity (in those days) to watch games on television. The Cubs and the White Sox had a full schedule of games on WGN Television (Jack Brickhouse did the play-by-play) and the Cubs were on WGN radio (Jack Quinlan, Vince Lloyd, and Lou Boudreau on the call), so every day I could watch or listen to a game. And since all of the Cubs’ home games were during the day, it allowed me to play in a variety of leagues in evenings. The broadcasters were both storytellers and reporters, a combination that fueled my interest in the people who played and worked in the game.

Did you dream of becoming a player yourself?

Without a doubt. I think all the guys in my neighborhood wanted to play in the major leagues. I wanted to play for the Cubs. I spent more time thinking baseball, playing baseball and learning baseball than I did any other activity in my life. Even when I was a young boy, baseball wasn’t a hobby – it was my life. And the Cubs were my favorite team. Anyone who knew me would tell you, the Cubs and baseball were my soulful passion.

You were able to work for your beloved hometown Chicago Cubs. Was that your dream job? And was it devastating to you when you lost it?

It was an honor to work for the Cubs and to go to “work” at Wrigley Field, but the opportunity came at a very traumatic time in my life. I was covering the Philadelphia Flyers and the National Hockey League for the Philadelphia Journal. The newspaper folded in mid-December of 1981. My son was six weeks old, my dad was dying of lung cancer back in Chicago, and my mom (who had never driven a car) was trying to keep it together and help my dad. I had made one mortgage payment on a 30-year house loan with an 18 percent interest rate. I had a lot of challenging life issues at that time. So the job, the income, the chance to return to my hometown and be with my dad and help my mom were the reasons for my gratitude. While working for the Cubs was a thrill for me, the other factors certainly took precedence.

It was very difficult to lose the job in late December – December 29 to be exact. There were not many baseball job openings that late in the off-season and I was without a contract. I had survived a melanoma cancer scare a few years earlier so insurance was going to be very costly for myself and for my family. At the same time, the organizational culture was changing and, in retrospect, as much as I loved the Cubs and loved walking into Wrigley Field every day, it was a blessing that it happened. It opened the door for me to move to the West Coast – first to San Francisco and then to Los Angeles. It may have been the greatest break of my career. Sometimes, we miss the blessings through the trials of life. The regime that changed the Cubs’ culture and my life was swept out 10 months later.

You write very candidly about your relationship with the owners who brought you to the Dodgers—the very controversial Frank and Jamie McCourt. But your relationship with them was quite nuanced. How did you manage to get along with them so well?

I have always worked for and respected high-powered, productive, relentless, and demanding people. I do not think someone rises to an ownership position or becomes the president of an organization without those qualities. It was important for me to learn how both Frank and Jamie worked, how they viewed the world, and what their expectations were.

While I did not always agree with them, I always found their perspectives instructive. Jamie and Frank were demanding but they also taught me a lot – about business, about relationships, about research and preparation. We do not always like the lessons we learn in life, but that does not mean the lessons were not worth learning. Sometimes you learn what to do; sometimes you learn what not to do. I relished the challenges and the conversations – the conversations always sharpened my thought process. While people read and form opinions from secondary sources, I try to always reserve judgment until I see it, hear it, or live it for myself. It was an incredible experience for me led by two very smart people. Was it challenging? Yes. Would any GM of a professional sports franchise say otherwise when they evaluated their own situation? No. I think every GM goes through challenges and trying moments with ownership. That the McCourt divorce proceedings were played out in public and not privately probably separated the experience from most others. It was the greatest learning experience of my professional life and that will always have value to me.

Having come to the Dodgers from their archrivals, the San Francisco Giants, how did you balance your affection for one team with your loyalty to the other?

My affection for people and respect for their friendships supersedes almost everything else. I did not grow up in either city so my allegiance was based on that team for which I was working. I did not, for example, develop a dislike for my friend Brian Sabean because I left the Giants. Individuals must be ultra-competitive to establish any measure of success in the professional sports world. And to be a leader of a baseball department, one needs an even greater dose of competiveness. This is our livelihood and there are only 30 baseball positions like this in the world. In 2014, the Dodgers won the NL West and the Giants finished second. It was a close race for most of the year. I always knew where to find Brian when we played in San Francisco and he always knew where to find me when the games were played in Los Angeles. That season, without a plan or conversation, we avoided each other. In fact, we never saw each other – not even once. Our respect for our positions, the organizations we worked for, didn’t need explanation. It is fierce. It is passionate. It is understood. The last words ether one of us wanted to utter to the other that season was a phony “good luck.” When the season ended, the first message I received was from Brian: “Well done.”

What is, in your opinion, the greatest trade you ever made? The worst?

Three trades stand out: Acquiring Manny Ramirez from the Red Sox on July 31, 2008 energized the team, the franchise, and the city of Los Angeles. The deal was not days or weeks in the making – it was made in hours. And Manny led us to the NLCS for the first time since 1988.

The second trade also came with Boston when we made the nine-player trade in August 2012 involving Adrian Gonzalez, Josh Beckett, Carl Crawford, and Nick Punto – and $250 million in payroll. There was so much more to that trade than just the players. It was about re-establishing the Dodgers’ brand in Los Angeles, new ownership stepping up in a big way, about marketing and tickets, and a pending local television contract that turned out to be historic in value to the franchise.

The third deal that comes to mind was my first deal as the Dodgers’ GM: acquiring a Double-A outfielder named Andre Ethier for a player who most agreed needed a change of scenery, Milton Bradley.

The worst deals I made were done with a lack of patience at the forefront: I signed Andrew Jones to a two-year contract as a free agent. Immediately, he was one of the most unproductive players in the game. I felt we needed a true center fielder and someone who could be a run producer. After we saw how he prepared and played, we still needed a true center fielder and a run producer. We also needed a front-line starting pitcher when I signed Jason Schmidt, who hardly pitched due to a shoulder injury. His entry physical had revealed some wear and tear on his shoulder but nothing unusual. It wasn’t until he underwent surgery that we discovered the severity of it.

Your parents were obviously strong influences on you. What did you learn from them that helped you as a general manager?

My parents were genuine, kind, and hard-working people. They struggled financially every day and never groused about it. Instead, they worked hard to overcome it. They knew it was not anyone else’s responsibility. They showed my brother and me how to work, how to be selfless, how to put others’ needs ahead of our own. I learned the value of respecting what I earned, and how to respect spending. Certainly, baseball’s contract world doesn’t resemble the street-corner-wise-guy hustle – but wisdom, the ability to read people, and measuring situations, are universal.

When it came to decision-making, my parents were methodical and thorough. They could not, literally, afford to make a mistake. I tried to be methodical and thorough as well, although sometimes the timing of a decision had a very short window.

I also felt I needed to live up to the standards they set throughout their life. I never counseled them once about a baseball decision; but I thought about them and what they would do pretty much every day.

What is it about your personality that has helped you succeed in a very tough profession?

I never take anyone or any part of life for granted. So while all my decisions were not successful, they were all done with much consultation and internal deliberation. And even though player contracts are at a very high level, growing up without much financial wherewithal gave me an appreciation for the value of the money at stake. In order to have any measure of success and survival, I have also had to be relentless and competitive throughout my life. Nothing ever came easy to me, but I never quit caring or trying. I will compete to the end.

It becomes clear from reading the book that you have great admiration for certain players—who are some of the favorites?

There are many – and too many to list here. I admire the grace, work ethic, and class of Andre Dawson and Ryne Sandberg; the 30-plus-year true friendship with Rick Sutcliffe; the hitting-genius of Barry Bonds, the pitching genius of Greg Maddux, and the overall baseball genius of Omar Vizquel; the relentless pursuit of perfection of Clayton Kershaw; the relentless and dogged approach of Jeff Kent; the winning, competitive spirit of Kirk Rueter; the style of Dennis Eckersley; the young minds of Corey Seager and Cody Bellinger; the maturity spurt of Kenley Jansen; the attention to the finest details of their craft of Billy Mueller and Jose Vizcaino, Mark Sweeney, Aaron Sele, Juan Castro, Josh Bard, John Vukovich, Manny Ramirez, Zack Greinke, and A.J. Ellis; the exuberance of Shawon Dunston and Juan Uribe; from my childhood days, I admire Ernie Banks, Billy Williams and, my all-time favorite, Ron Santo; and a host of players who I never doubted gave the game everything they had to offer, whether they were making a dollar or $30 million.

With the benefit of hindsight, and knowing the pros and cons that the job entails, would you want to be a general manager again? And are you glad to have moved on in a new direction?

One of the many life lessons I learned during my Dodgers’ career was realizing what I did not have control over and what I had very limited control over. In the right situation, with honorable people and with a chance to grow a franchise and others’ careers, I would love to be a GM again. At this point, I would not do it just to do it. I have also found the television baseball analyst position to be a very rewarding one. I work with some of the best people I have ever been associated with and I enjoy the challenge of doing something I had never done before. Additionally, the blessing to be able to teach, mentor and learn from the people who comprise Pepperdine University has exceeded all my expectations. Candidly, I could not have afforded to attend an institution like Pepperdine, nor did I have the educational requirements to be admitted. Invited to be a part of Pepperdine is one of the greatest, albeit unexpected, honors of my life.

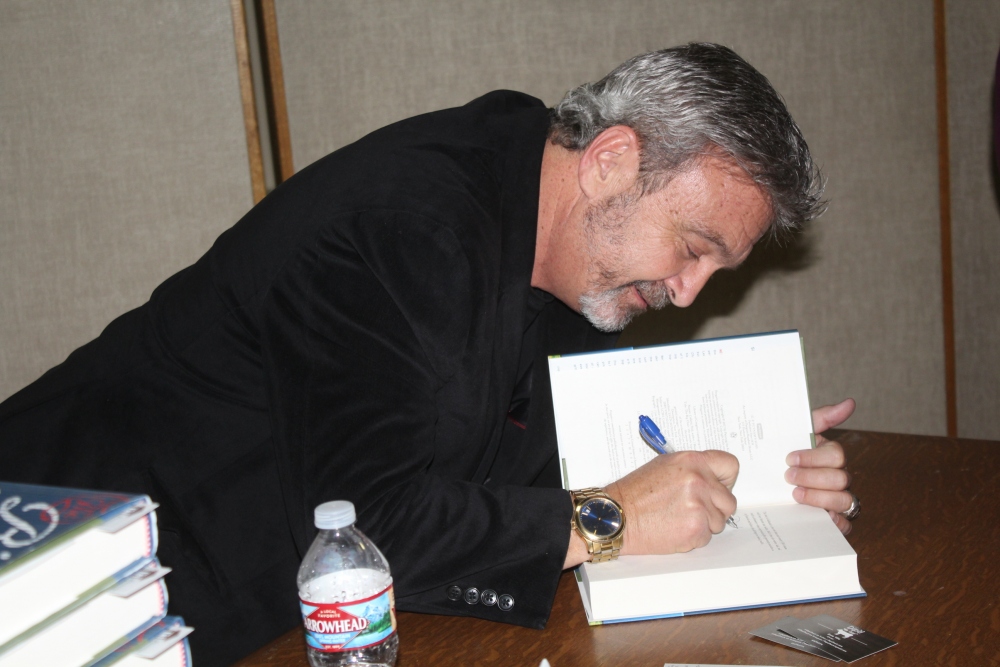

When you set out to write The Big Chair, did you have an end goal in mind?

My goal in writing this book was fairly simple: to pay forward all of the storytellers who helped sow the love of the game in me. Maybe there is a person who reads the book and develops a deeper love for the game or a newfound interest. I also hope to give confidence to young people who wonder if they can accomplish their dreams. I was not a great student in school and I did not have parents or friends who were networked into a profession where an opportunity was forthcoming. I had to work at it every day and I needed to be blessed beyond measure in order to have any chance. Lastly, I wanted to open the door to the office that many people are interested in, one very few will ever truly understand and one that is often misunderstood.

What would you say is your own legacy to the game?

I’m not sure if a legacy is self-defined or defined by others. I have helped organizations – along with a great combination of teammates – to be successful, entertain, and win. And I have cared about many people and placed them ahead of myself and, sometimes, ahead of my family. But I remember watching a press conference near the end of the 1980 baseball season: Don Zimmer, who later would become one of my most profound teachers of baseball and one of my best friends, had been let go as the manager of the Red Sox. He was asked how would he want Boston fans to remember him. He paused for a second, checked his emotions that were beginning to show through tears, and said: “I’d like to be remembered as a good man.” I feel the same way.

For more information on THE BIG CHAIR and Ned Colletti please visit:

.png)