In 1883 (before the City of South Pasadena was incorporated), local area boosters published the book “A Southern California Paradise” to make the case that San Gabriel Valley (Pasadena, San Gabriel, Sierra Madre, La Canada) was a virtual “paradise” on Earth.

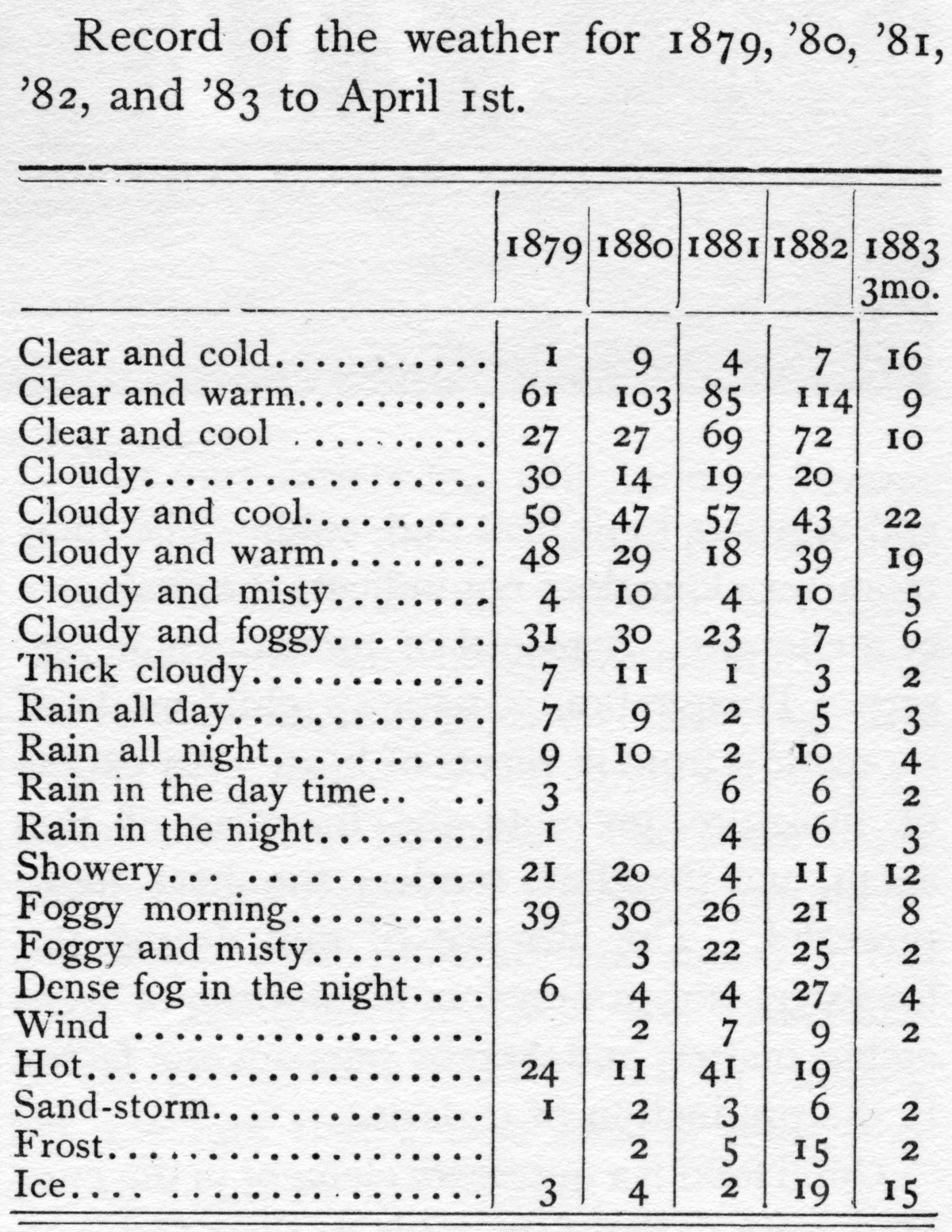

A complete four-year record from 1879 to 1882 shows how the clear-sky weather conditions might appeal to early Southern California travelers. The chapter on health benefits includes a doctor’s evaluation of known diseases: “More than half of the adults came here on account of ill health, and yet there is comparatively little sickness.”

Publications such as this stirred the interest of such entrepreneurs as Walter Raymond who owned the Boston-based travel agency Raymond’s Vacation Excursions.

Raymond scouted the area for the best winter conditions for his wealthy Midwest and East Coast vacationers, selecting South Pasadena to build his winter resort hotel.

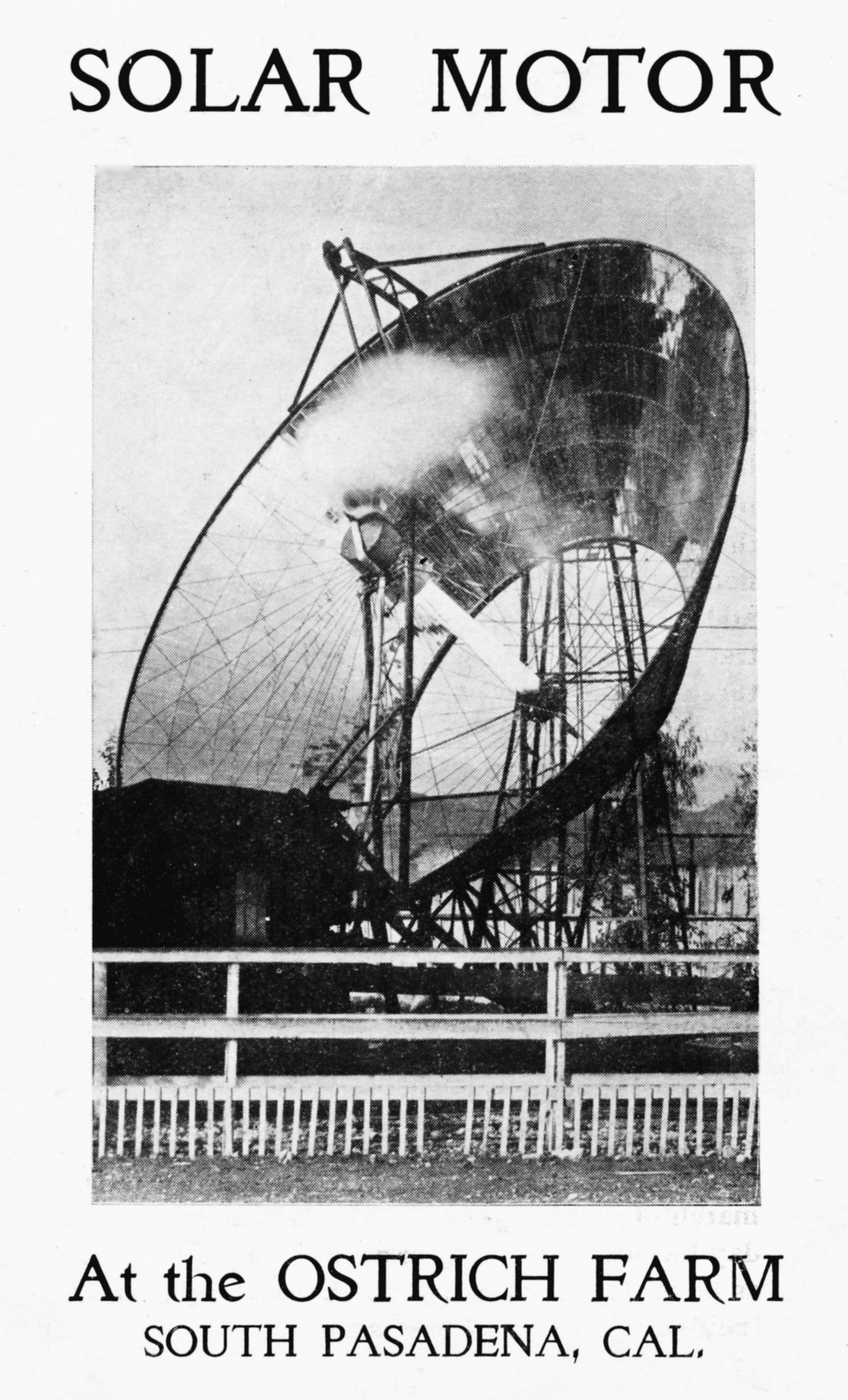

Aubrey Eneas selected Edwin Cawston’s ostrich farm in sunny South Pasadena to showcase his gigantic parabolic dish and launch his new company, Solar Motor Company.

In 1901, the Cawston Ostrich Farm was the site of the world’s first successful experiment using a solar-powered motor for commercial use.

It was an odd site for sure: Cawston’s flock of some 260 strange-looking birds milling around a towering mechanical beast with its 1,788 mirrors flashing in the bright sun.

The spectacle lured several newspaper and magazine reporters to the farm. They reported tales of the California ostrich farm to their Midwest and East Coast readers who were hungry for stories about the west. Cawston loved the free publicity as evidenced by his reprinting their comments in his advertisements, brochures, and catalogs.

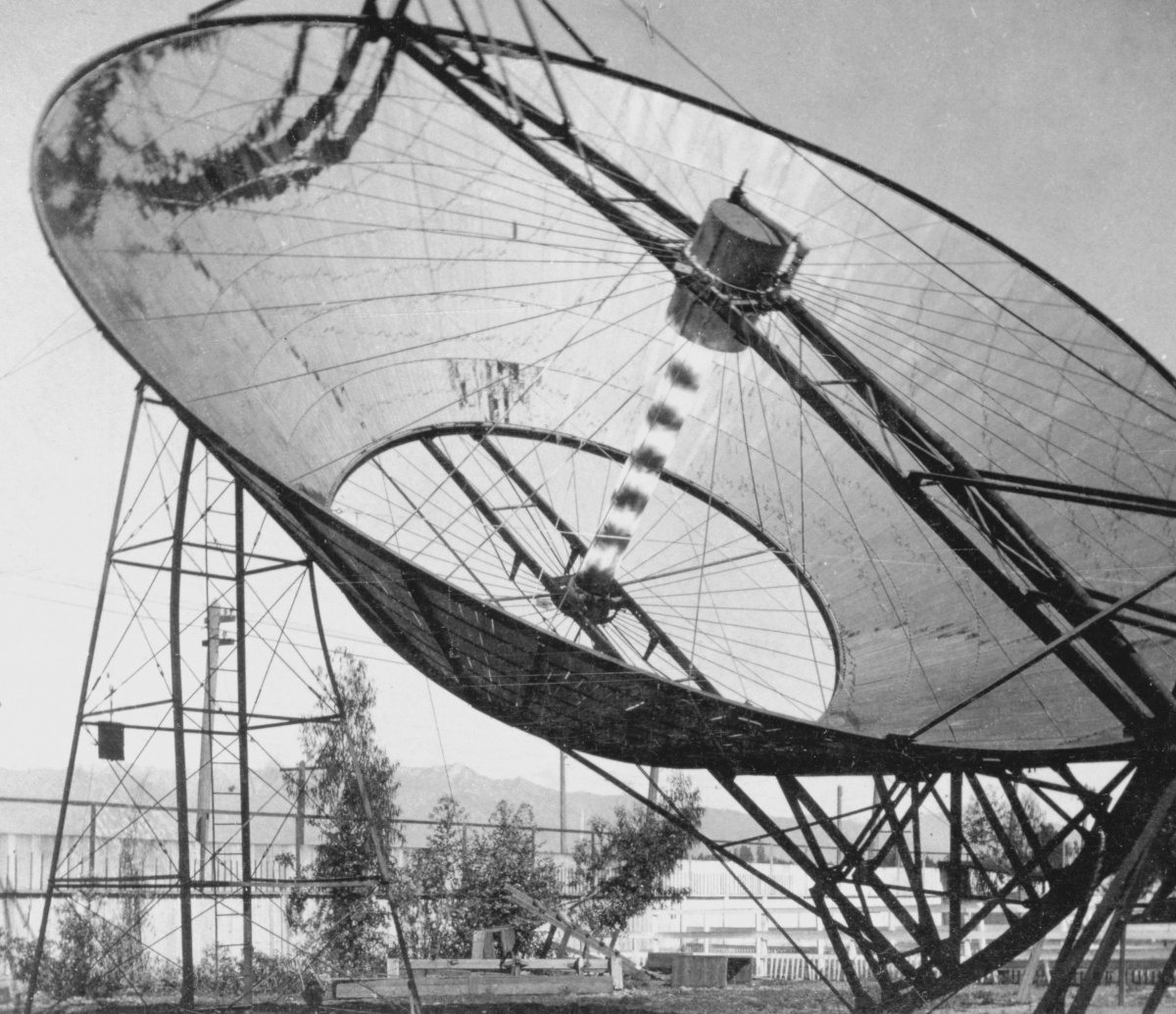

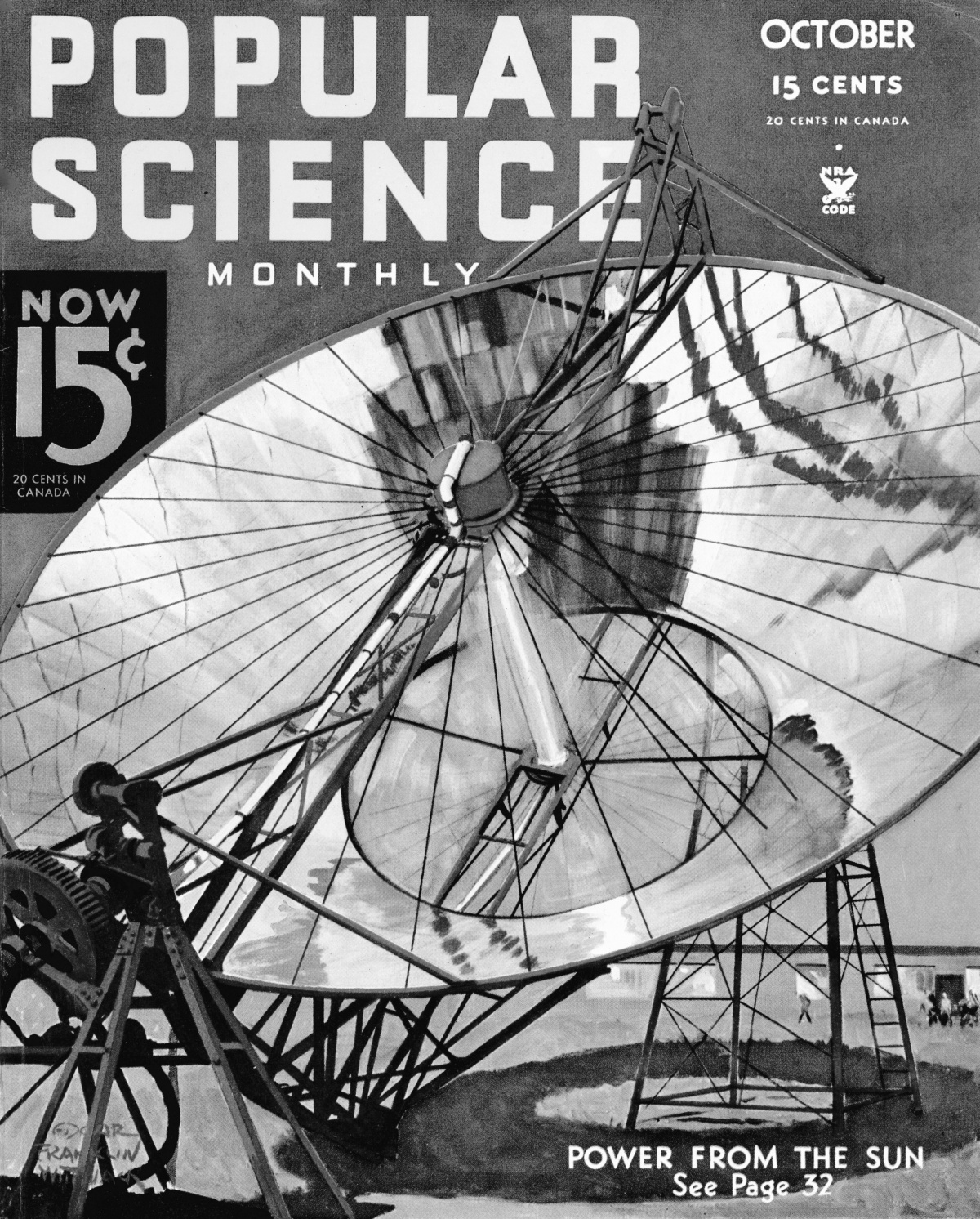

In 1902, Applied Science described The Solar Motor as “a sunflower, automatically keeping its shining face toward the sun. The morning dew is seen slowly to ascend in a wreath of vapor from its giant bloom.”

The Bradbury Building in downtown Los Angeles was the west coast headquarters for The Solar Motor Company. The massive “glass ceiling” allowed natural sunlight to pour into the interior of the office building underscoring the company’s claim that solar power is an ever-present resource.

According to an internal company memorandum dated December 8, 1903, the Solar Motor Company’s principal assets were the U.S. Patents Nos. 670, 916 and 670,917 (Aubrey Eneas, solar generators).

The solar motor consisted of a boiler 13 feet in length and a foot wide, containing 1,000 gallons of water. The solar mirrors were configured to focus concentrated light energy onto the boiler. The water boiled and transferred steam to an engine that pumped 1,400 gallons of water per minute from a deep well on the Cawston farm.

The umbrella-like “dish” was heavily ribbed with steel and cradled in a tall iron framework, like that set up for windmills. Under the bottom of the dish was an equatorial mounting, similar to the yoke-action apparatus used with large astronomical telescopes.

The solar motor was balanced, the weight distributed evenly over roller bearings so that only a slight of energy is required to keep it facing the sun for automatic tracking throughout the day.

Several pulleys and cables were utilized in this design to take full advantage of the physics of leverage to move the mirror-laden dish easily in its iron “cradle” framework.

Speculation ran high for the future of such a plentiful, low-cost energy source. One such article titled Harnessing the Sun (F.B. Millard, 1901) proclaimed: “Why should we burn costly, hard-delved coal in power-houses when we can hitch our trolley cars to the sun?”

In a letter from the Solar Motor Company dated April 20, 1903, the cost of fuel (coal vs. solar) to produce power is compared based on running a steam engine to pump 700 gallons of water a day.

Coal-fired boiler: Initial cost is $600. The annual fuel expense of coal ($20 per ton) is $1,800 plus $365 attendance fee

Solar Motor: Initial cost is $7,200 (three solar motors). The annual fuel expense of solar power (free) is $0 plus $55 attendance fee

The Solar Motor Company’s motto: SUN is our FUEL

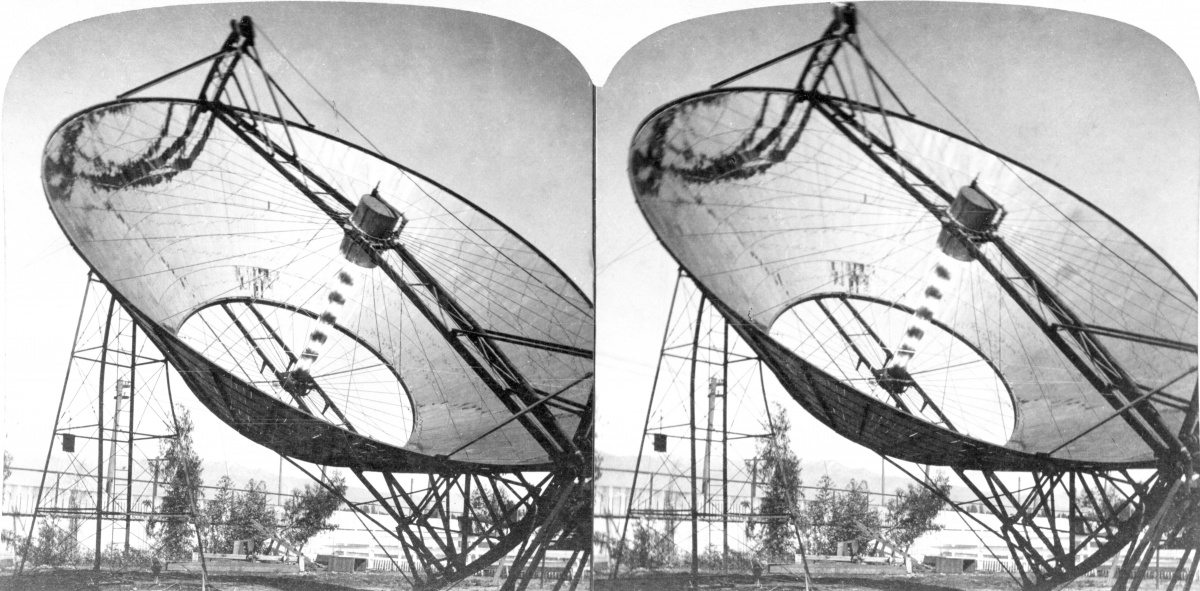

The above stereograph photo offers the best picture of the solar power experiment as a three-dimensional view.

Note: To view stereographs in 3-D without the aid of a viewer, merely look at the image at a comfortable viewing distance and cross your eyes slowly until the two images merge into one three-dimensional view.

The Solar Motor required considerable space and sufficient sunshine to make it viable. Both were available in South Pasadena on the ostrich farm.

However, with inexpensive fuel production on the rise from easily accessible oil fields, the solar motor was doomed from the start. Furthermore, the solar motors were touted to resist high desert winds, but not the hail storm in 1903 that destroyed the solar motor on a ranch near Mesa, Arizona.

.png)