When Lori and Grant Davis-Denny purchased the historic Garfield House in South Pasadena in 2015 for $3 million, they knew they were taking on a sacred legacy.

“We look at ourselves as stewards of the house,” said Lori Davis-Denny, of the Garfield House and whose third child, Edison, was born a day after they moved in. “We wanted to restore the property and we wanted to do it the right way.”

But while dedicating themselves to a plan of restoration and improvement, the Davis-Dennys didn’t realize that completing their vision for the famous landmark would require enlisting help from an unlikely ally: Caltrans.

South Pasadena’s decades-long staredown with the state’s freeway builder has been rocky at best. But in this case, the agency–particularly staff in its District 7 Right of Way and Environmental Analysis division—helped the couple resolve obstacles created by a troublesome empty lot left over from Caltrans’ ill-fated quest to build an extension of SR-710 through this small hamlet.

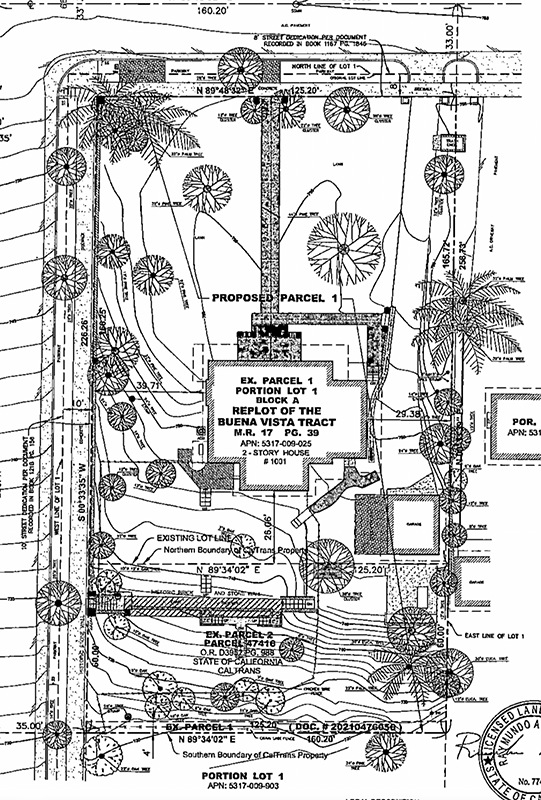

The cultural and historical pedigree of the 4,100-square-foot Garfield House, completed in 1904 on a half-acre corner lot at Meridian Avenue and Buena Vista Street, is unassailable.

The two-story, Craftsman-style Swiss chalet was designed by legendary architects Charles and Henry Greene – ‘Greene & Greene’, credited with designing the definitive California houses of the American Arts & Crafts movement. It was built for the extended winter stays of Lucretia Rudolph Garfield, a distant cousin of the Greene brothers and widow of James A. Garfield, 20th President of the United States–a Civil War hero who fought patronage in the days before the ‘civil service‘ and died of an assassin’s bullet in September 1881, six months after taking office.

A storied set of five dozen, handwritten letters document what Greene & Greene historian Ted Bosley has called the friendly “battle of wills” between the widow Garfield and Charles Sumner Greene—both natives of Ohio—over the cost and many design particulars of the house.

“It was a delicate dance of social niceties for sure,” said Davis-Denny, who’s studied and become a fan of the former First Lady. She said Garfield was a well-educated, proto-suffragette of modest extraction. She finds the letters entertaining, extolling Garfield’s “very flowery and nice cursive writing [when] really what she’s saying is: ‘I’ve decided I want to change the entire floor plan, at no additional cost of course!’”

Garfield made improvements to the home until her death there in 1918.

Ownership then passed through a line of colorful characters including:

- W. J. MacDonald, a well-known Chicago investment broker and president of Pasadena’s Annandale Golf Club;

- Walter S. Heineman, a dabbler in real estate and lyricist who held joint copyrights for songs composed with musician Justine Gilbert, and whose younger brothers, Pasadena architects Arthur and Alfred, are considered among the most prolific practitioners of the California Arts and Crafts movement after Greene & Greene (Arthur coined the word “motel”). Walter’s wife, Irene T. Heineman, served over 15 years as the California State assistant superintendent of public instruction, and was the first president of the Los Angeles League of Women Voters;

- Francis Lackner, a prestigious retired Chicago attorney and Union Major who was wounded at the battle of Gettysburg;

- George R. Reinicke, a travel agency owner who married Lackner’s daughter;

- Andrew Evert Chute, a petroleum industry chemical engineer who lived there over 50 years while raising ten children;

- Artist Melanie Ciccone, sister of Madonna and spouse of singer-songwriter Joe Henry, who together undertook a massive rehabilitation of the home’s interior and installed a basement recording studio where film scores and over two dozen albums were recorded by artists such as Kris Kristofferson and Bonnie Raitt.

By 1964, the Garfield House was within an area of intersecting ramps targeted to serve the proposed 710-freeway extension. In 1974, it was described by the local paper as among the homes “in the path or dangerously close” to the proposed Meridian route alternative for the would-be freeway. Then owner Andrew Chute told the L.A. Times the Meridian route would run through his backyard. Like other savvy South Pasadenans, he worked to frustrate Caltrans’ plans by getting the Garfield House listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

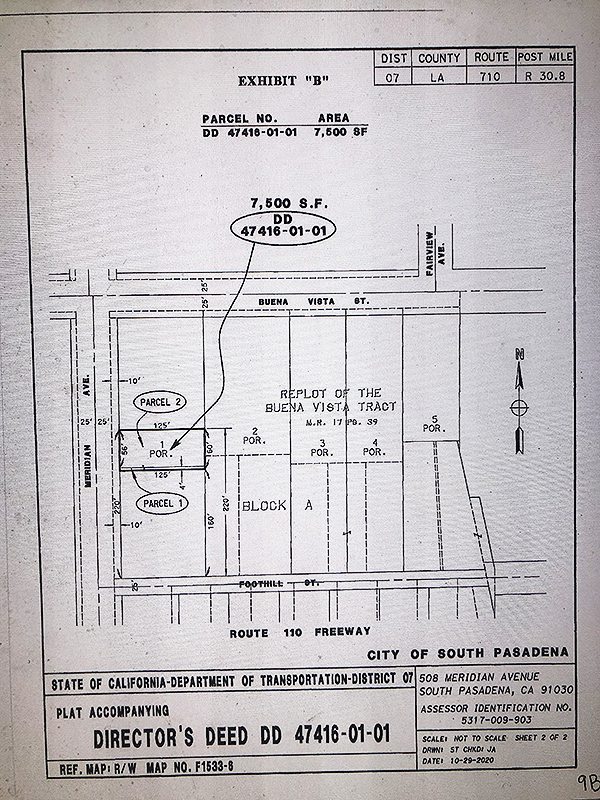

Davis-Denny said it was Chute who, sometime in the mid-1960s, sold a portion of that backyard–a 7,500-square-foot lot immediately south and down slope of the Garfield House–to a fellow who turned around and sold it to Caltrans.

She said Mr. Chute’s sale of the lot did not go down well with his wife. “We’ve been told Mrs. Chute did not speak to Mr. Chute for over a year!” Apocryphal or not, there’s no doubt Therese Chute’s wariness over the sale was prescient.

The person who bought the lot was Dudley E. Sorenson, a kind of 20th century Renaissance man who was a baker, veteran, gardener, carpenter, consultant, and successful land developer with over 30 years in the Los Angeles Fire Department–including many as an assistant chief. He didn’t live in town, but his son Steve Sorenson recalls that his dad supplemented his early years’ LAFD income with gardening work in South Pasadena.

The circumstances of Sorenson’s purchase of the lot are hazy. But it is believed he repeatedly approached Andrew Chute, who finally agreed to sell it to him, either as a favor or business proposition.

Records show that in July 1962, Sorenson secured city approval to subdivide the Garfield parcel to create the new 7,500 square-foot lot. The subdivision was conditioned on his moving an existing garage north, closer to the Garfield House, which was done. The following November—the same month concrete was poured for the relocated garage–a deed of trust was recorded under which Chute sold the new lot to Sorenson for $4,000 and agreed to make him a construction loan of up to $25,000.

But nothing was ever built.

Though away at college at the time, Martha Fitzpatrick, Chute’s eldest child, recalls that after the sale, a dispute arose over whether the new lot was buildable.

In September of 1963, Sorenson sought to sell the lot through a real estate broker who included it on a list of available properties in a newspaper ad. But nine months later, the lot appeared on another published list, this one of properties subject to state forfeiture due to delinquent taxes. Sorenson owed $121.66. The amount grew until March of 1968, when Sorenson sold the lot to Caltrans for $14,355.35.

More recently, the California Transportation Commission summed things up saying the property was subdivided “due to an inherited dispute with prior owners.”

In the decades that followed, memory of the state’s acquisition of the lot and its boundaries faded–though Fitzgerald said Caltrans’ ownership was disclosed when her family sold the Garfield House to the Ciccones in 2006.

As Davis-Denny tells it, Melanie Ciccone was looking out the window of the Garfield House sewing room one day when she saw someone hop the fence and proceed to mow down bushes in her backyard.

“She runs out there screaming, ‘What are you doing? This is my yard! And they inform her, ‘No, this is not your land,’ and that is how she found out Caltrans actually owned the property.” So the Ciccones signed a deal to lease the Sorenson lot from Caltrans. The lease was renewed when the Davis-Dennys bought the Garfield House.

Lot Slows Restoration

Dudley Sorenson’s lot proved to be an obstacle to the Davis-Dennys’ restoration vision. Though legally unimproved property, it includes landscape and hardscape features designed by Greene & Greene, including a prominent outdoor staircase and walkway, and part of a wide, arroyo stone retaining wall that runs much of the western length of the Garfield parcel.

Further, just below the Sorenson lot is another parcel along Meridian Ave. on which, Davis-Denny explains, a previous Garfield House owner built a house for a family member. As a result, elements of the two houses are connected, most notably by a 100-foot-long cast iron sewage pipe that by 2015 was in such disrepair, it too became part of the restoration project.

“But” Davis-Denny asks, “how to do that when we have to negotiate with Caltrans to fix the sewage line, reroute to the street, and negotiate with the neighbors below, who are also doing construction on their house?”

In addition, there are protected trees growing on the lot. Still another complication arose when a survey showed the north end of the Sorenson lot came much closer to the Garfield House than any of its recent owners knew.

Holding the lease would not be enough: completion of the restoration would require ownership of the Sorenson lot.

But even with the final demise of the 710 extension and tunnel options, Caltrans’ list of properties for disposal did not initially include the Sorenson lot and it could be years before it would. The historical restoration of the Garfield House was put on an indefinite hold.

Preservationists to the Rescue

By this time it was 2018 and Davis-Denny was in touch with the South Pasadena Preservation Foundation. Honorary SPPF Board Member Glen Duncan shared with her his extensive knowledge of the Garfield House, advised on how to secure support for restoration through the Mills Act, and helped strategize on approaching Caltrans about securing ownership of the Sorenson lot through the agency’s labyrinthine surplus property disposal procedures.

SPPF board members – all volunteers, provided contacts at Caltrans and the city, enabling improved communication that moved the process along. For example–in an echo of the old dispute over Sorenson’s purchase of the lot in 1962–the city told Caltrans it was suitable for a 2,200-square-foot house. That may be how it looked on paper, Davis-Denny said, but in fact the slope, existence of protected trees, and presence of the historical staircase and retaining wall, all indicated otherwise.

The city data drove the eye-popping estimate Caltrans included in its initial appraisal. “After throwing up,” Davis-Denny laughed, and with intervention from then Mayor Richard Schneider, the city’s planning department conceded it would never approve a building permit for the lot. Caltrans appraisers then agreed to a site visit. Once they’d researched the extent of the historical covenants and other development constraints, the estimate came down.

“At that point, they were on our side,” Davis-Denny said.

The agency began to “rethink” the situation, agreed Ed Francis, then Caltrans Deputy District Right of Way Director. Simultaneously, as it became clear neither the surface nor tunnel options for the 710 extension would proceed, Caltrans’ need for the Sorenson lot and other parcels along the 710 extension route abated.

“The goal of Caltrans is to sell any property that is not needed for a project or for operational needs,” said Francis. That enabled it to commence its process for the sale of vacant lots to leaseholders. It also helped that Francis had been involved in preparing the lease the Davis-Dennys signed for the Sorenson lot when they bought the Garfield House.

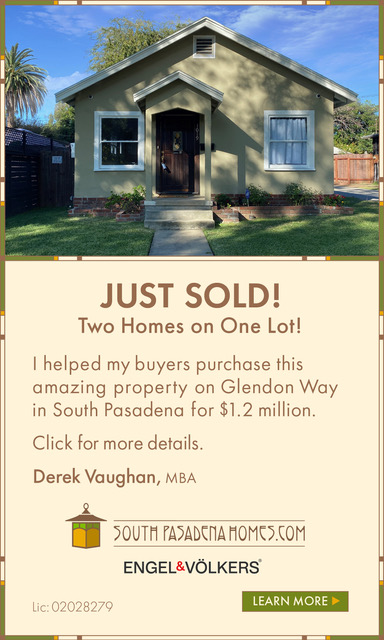

In a letter supporting the sale, SPPF President Mark Gallatin cited additional assistance from Caltrans’ staffers Doug Hoover, Howard Kuo, and Kelly Ewing-Toledo as having been “particularly instrumental in the success of this sale.” The California Transportation Commission approved the sale of the Sorenson lot in January 2021 for $50,000, and the city formally approved reunification of the parcel in March 2022.

After Caltrans came through, it took two more years to secure permits from the city. But the restoration project is “on-going,” the Davis-Dennys report. While the retaining wall has proven insufficiently stable to sustain all but cosmetic improvements, restoration of the long, Greene & Greene walkway from the sidewalk to the front porch—using original bricks—has been completed. It is hoped these and other prospective improvements—such as a swimming pool and new covered patio–will soon serve to further enhance the Garfield House legacy.

.png)